Wildlife trafficking is not just an environmental issue – it is a criminal economy worth billions.

Image: Grok

South Africa’s natural heritage is under siege from organised crime, weak regulation and murky legal markets.

From vaults holding rhino horn stockpiles to pens of captive-bred lions, and from the elusive pangolin to plundered seas, an expanding illicit wildlife economy is eroding biodiversity, undermining sustainable livelihoods and fuelling transnational criminal networks.

Legal loopholes, under-resourced enforcement agencies and the high value of wildlife products have created fertile ground for trafficking syndicates, allowing them to move endangered animals and derivatives across borders with alarming efficiency.

The consequences reach beyond conservation: local communities are left vulnerable, ecological systems are destabilised, and South Africa’s global reputation as a leader in wildlife protection is increasingly at risk.

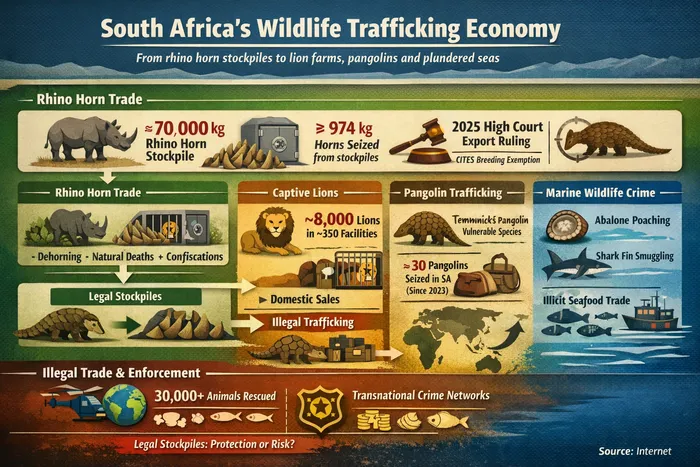

South Africa holds one of the world’s largest rhino horn stockpiles – legally accumulated from horns harvested in dehorning, natural deaths and confiscations.

Official disclosures from government Promotion of Access to Information responses from the Department of Environment, Forestry and Fisheries (DFFE) obtained by the EMS Foundation in mid-2024 show government holdings of about 27,650 kg and private holdings at roughly 47,500 kg. This accounts to around 70,000 kg of horn.

The legal regime allows domestic trade under strict permits, while international commercial trade remains prohibited under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) and domestic implementing law, the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEMBA).

Yet, Jason Gilchrist, lecturer in the School of Applied Sciences at the Edinburgh Napier University, has said that “diminishing demand for rhino horn would ultimately remove the incentive for poaching rhino. It would also remove any incentive to private landowners to farm rhino for their horn.”

Between 2016 and 2021, at least 974 kg of seized rhino horn were forensically traced back to legal stockpiles, demonstrating leakage into illicit channels, according to EMS Foundation research.

A seven-year investigation by the South African Police Service’s Hawks and DFFE culminated in the arrest of suspects linked to 964 horns destined for illegal export, confirmed in a government media release.

South Africa's wildlife tracking economy.

Image: ChatGPT

Then DFFE Minister Dion George said that this “complex investigation… is a powerful demonstration of South Africa’s resolve to protect its natural heritage. The Hawks’ work shows that our enforcement agencies will not hesitate to pursue those who plunder our wildlife for criminal profit.”

George added that “the illegal trade in rhino horn not only destroys biodiversity but also undermines the rule of law and the foundations of environmental governance”.

In 2025, the High Court in the Northern Cape delivered a ruling interpreting a captive breeding exemption in CITES to potentially allow horn exports under narrow conditions.

The EMS Foundation has previously noted that “instead of destroying the rhino horn after removal, South Africa has chosen to continue the risk to the diminishing surviving rhino population by driving the perception that the horn has value and stockpiling it… It is inevitable that rhino horns from stockpiles will flow into the international illegal trade.”

South Africa is at the centre of one of the world’s most contentious wildlife industries: controlled lion breeding for hunting, tourism and bone export.

An estimated 7,800 to 8,000 lions are held in captivity across more than 300 facilities, according to research from the Ministerial Task Team and NGO estimates.

A Ministerial Task Team was appointed in December 2022 to recommend pathways for a voluntary closure of captive lion facilities. But, recently, the current Minister of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment – Willie Aucamp – said he was still awaiting comprehensive implementation plans before taking further steps, amid allegations of industry ties he denies.

Captive breeding of lions has underpinned “canned hunting” – hunts in confined spaces where escape is impossible. Lion bones, like rhino horn, are sought in some Asian markets for purported medicinal value, despite no scientific basis, according to animal welfare organisations.

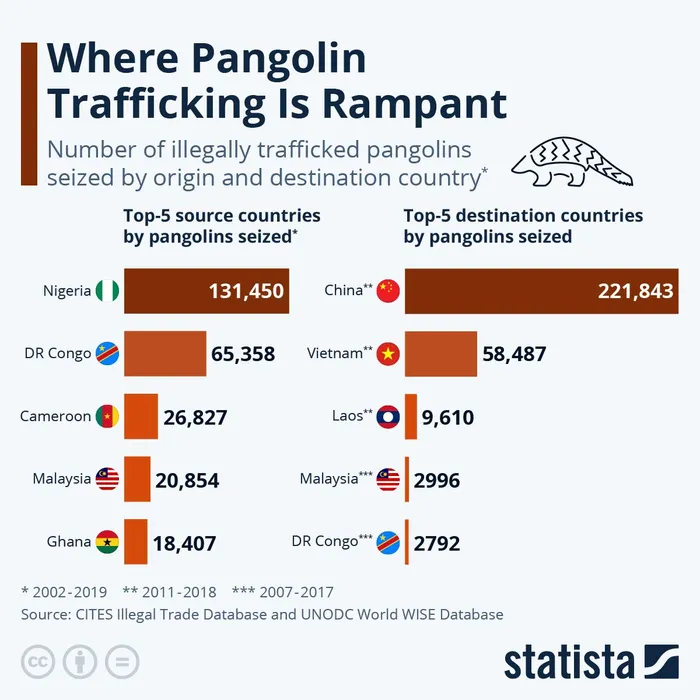

Where Pangolin trafficking is rampant.

Image: Statista

The Temminck’s ground pangolin, South Africa’s only indigenous pangolin species, is listed as Vulnerable and protected under domestic law and CITES Appendix I.

From January to August 2023, around 30 pangolins were seized in the country, primarily live animals, according to EMS Foundation data.

A ScienceDirect article from last year found that interceptions of pangolin scales from Africa to China have increased remarkably in recent years totaling 6.4 tonnes, 6.3 tonnes in 2015, 18.9 tonnes in 2016, 46.8 tonnes in 2017, 39.7 tonnes in 2018 and more than 97 tonnes in 2019.

"As the four Asian pangolin species have become even more scarce, the demand for pangolin scales has in turn increased in Africa at industrial levels in order to supply the Asian market demands," it said.

Marine wildlife also plays a role in the illegal wildlife economy. South African abalone (perlemoen), prized in East Asia as a luxury seafood delicacy, is among species heavily targeted by illegal harvesters and organised syndicates.

Although commercial abalone fishing was banned in 2007, enforcement challenges have allowed illegal sea harvesting and smuggling to flourish, with gangs working with foreign networks to export dried abalone to lucrative destinations, analysis by governance and fisheries organisations shows.

Perlemoen, shark fins and other marine products are among the broader suite of illicit wildlife commodities trafficked across borders, reinforcing how marine crime intersects with terrestrial organised trafficking networks.

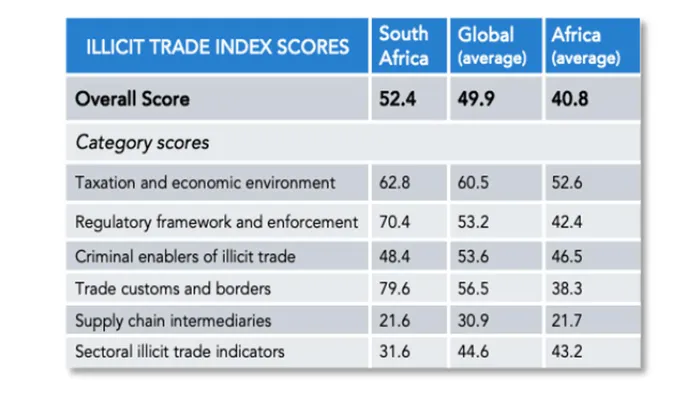

How South Africa's illicit trade stacks up globally.

Image: Tracit

Wildlife trafficking is not just an environmental issue – it is a criminal economy worth billions. Global enforcement demonstrates this: Interpol’s Operation Thunder 2025 rescued nearly 30,000 trafficked live animals and seized tons of wildlife products.

“Nearly 30,000 trafficked live animals were rescued during coordinated operations against wildlife and forestry crime, and tons of wildlife products were seized,” said Interpol.

Conservation groups argue that eliminating stockpiles, closing controversial breeding industries and enhancing coordinated enforcement are essential to stop legal markets being co-opted by illegal networks.

As Ministers await internal reports and court appeals, the stakes extend beyond borders. South Africa’s policies on rhino horn exports, captive lion facilities and wildlife trade enforcement will influence ecological outcomes, criminal justice, economic development and international reputation.

The wildlife underworld – linked to transnational crime and corrupt incentives – will continue to threaten biodiversity unless legal loopholes are closed and enforcement prioritised alongside sustainable community livelihoods.

IOL BUSINESS