The alarming rise of child offenders in KwaZulu-Natal

Nearly half of South Africa's sentenced child offenders come from KwaZulu-Natal, highlighting the urgent need for community support and effective rehabilitation strategies to combat the cycle of poverty and gang violence.

Image: File

KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) is grappling with a profound social crisis, holding the unfortunate distinction of having the highest number of children under 18 sentenced to correctional facilities in South Africa.

While national figures on child incarceration show a recent upward spike, KZN remains the epicentre, a grim reflection of deep-seated poverty, gang violence, and systemic challenges that are failing the province's youth.

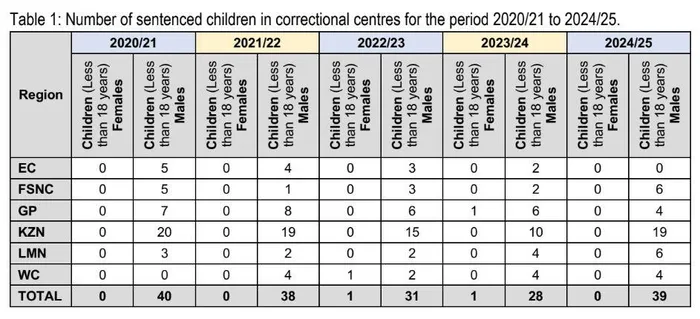

According to data from the Department of Correctional Services (DCS), the national number of sentenced children under 18 has fluctuated, showing a general downward trend before a recent spike.

The total number dropped from 40 in the 2020/21 financial year to its lowest point of 29 in 2023/24, but the most recent figures for 2024/25 reveal a sharp increase back to 39, all male.

KZN, however, has consistently led this statistic, with figures ranging from a high of 20 in 2020/21, dropping to 10, before surging again to 19 in the current 2024/25 period.

This indicates that nearly half of the country’s sentenced child offenders are incarcerated in just one province.

Statistics from the Department of Correctional Services highlight the alarming trend of child incarceration in KwaZulu-Natal, revealing that nearly half of South Africa's sentenced youth offenders are from this province.

Image: Supplied

DCS spokesperson Singabakho Nxumalo lists the offences as a catalogue of serious violence: “rape, robbery with aggravating circumstances, murder, robbery, culpable homicide, attempted murder, intentional assault, theft, contravention of the immigration act, and possession of a firearm and ammunition.”

The story of KZN’s escalating child offender numbers is interwoven with the brutal reality of gang and drug-related violence that has become entrenched in areas like Wentworth in Durban, where shootings and turf wars are a common occurrence.

Here, a desperate “vacuum” created by years of lethal feuds has opened the door for drug lords to actively recruit children as young as 13 and 14.

A long-time Wentworth resident, who requested anonymity for fear of reprisal, painted a chilling picture of the area's recruitment drive.

“A whole generation of people who would have been in their twenties has been wiped out by the killings and shootings over the years,” the resident explained. “As a result of that ‘vacuum’, the drug lords are now recruiting younger and younger children — they call them ‘soldiers’.”

The lure for these vulnerable youth, often living in poverty-stricken communities, lies in the perceived glamour of a criminal life.

“There's a whole hype around it. They see drug lords driving nice cars, their reputations precede them, and the kids are eager to prove themselves,” the resident said.

This recruitment is far from harmless; it is sealed with an act of violence. “These soldiers are required to prove themselves… They have to be able to take a life. They call it their 'duty',” the resident stated. “That’s how they know that they can trust you. If you’re able to carry it out, then you go to the next level.”

The resident also highlighted the terrifying escalation in deadly violence and the lethal environment these children are operating in. “Before in Wentworth, if you had handguns, it was a big thing, but today they are using automatic assault weapons. That’s not normal,” he added.

Poverty is identified by community members as the single biggest driver.

“Poverty is the biggest problem that we have in Wentworth, and there are no resources,” the resident stated, pointing out how even the elderly become willing participants.

“They use old ladies’ houses as safe houses. The old ladies are battling on a pension, so if someone comes and says, ‘Hey, I’ve got another couple thousand rand for you every month,’ because of circumstances, they agree,” he said.

For those who attempt to escape, the consequences are often fatal. “The moment someone says they want to get out, they want to throw in the towel to change their lives, their own circle will kill them because they know too much,” the resident warned. “Reforming your life is taken as betrayal.”

The resident recalled the harrowing fate of one dealer who had left the life of crime. “They waited for him outside of church, and he came out on a Sunday evening, and they gunned him down.”

The problem is compounded by a complex gang hierarchy that extends even into the prison system, where loyalty is maintained through ranks, where they are required to carry out different tasks, he said.

While KZN’s incarceration numbers are high, the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) notes that efforts are under way to use the Child Justice Act (CJA) as a tool for rehabilitation over punishment.

NPA spokesperson Bulelwa Makeke acknowledged a “moderate increase in the number of child offenders being arrested, particularly for offences related to assault, theft, and drug-related activities”.

However, Makeke was quick to point out that this increase has been met with “improved screening and case management processes under the Act, which ensures that only matters meeting the threshold for prosecution are enrolled”.

The NPA is working closely with the police and probation officers to ensure “diversion options are considered at the earliest stage possible”.

Makeke emphasised the transformative impact of the CJA. “The implementation of the Child Justice Act has significantly enhanced the manner in which children in conflict with the law are treated,” she said.

She said this is reflected in a “steady increase in the number of matters diverted, reflecting the Act’s focus on rehabilitation and restorative justice”.

Diversion, however, is not an option for all. Makeke stated that in cases involving serious offences— such as murder, rape, robbery with aggravating circumstances, and assault with intent to do grievous bodily harm — the NPA generally pursues formal prosecution.

“Such offences are considered too severe for diversion… as they involve significant harm to victims and the broader community,” she explained.

Even in these serious cases, the NPA strives for a trial process that “remains child-sensitive, with consideration given to the child’s developmental needs and potential for rehabilitation”.

Adding to the NPA's efforts, Makeke noted that while some provinces experience delays due to case backlogs in the child justice system, the NPA continues to “prioritise child-related matters to minimise secondary victimisation and ensure speedy resolution”.

To achieve this, “dedicated child justice courts, trained and specialised prosecutors have been established in several jurisdictions to expedite the handling of these cases”.

For those children who are sentenced, like the 19 currently in KZN's facilities, the Department of Correctional Services insists on a rehabilitative approach.

Nxumalo noted that the number of children being incarcerated “fluctuates within the same range and it would therefore be inaccurate to suggest that they are increasing. However, it remains deeply concerning for any child to be incarcerated, as this reflects broader societal challenges in guiding and supporting young people who come into conflict with the law.”

Nxumalo stressed the separation from adult inmates and the commitment to education and support.

“They are strictly separated from the adult inmate population to ensure their safety, dignity, and developmental needs are prioritised,” he said.

Each child receives an individualised Correctional Sentence Plan based on a comprehensive assessment, with access to social workers, psychologists, and occupational therapists, who provide “emotional support, trauma counselling, behavioural interventions, and developmental guidance aimed at addressing the root causes of offending behaviour and strengthening resilience”.

Beyond formal education through continuous schooling, life skills, recreation, and sports are also incorporated to support healthy development and encourage positive behaviour.

He said it is not a one-size-fits-all approach that supports their successful reintegration back into society.

“Children in custody still have the opportunity to change the course of their lives, which is why it is critical that they are supported, guided, and directed towards positive pathways,” Nxumalo concluded.

The Wentworth resident issued a stark warning, appealing to young people to steer clear of this industry. He cautioned that escaping once involved is impossible without significant financial means.

Have thoughts on this topic or other subjects you’d like us to explore? Want to share your experiences? Reach out to me at karen.singh@inl.co.za – I’d love to hear from you!