The cover of William Kelleher Storey's biography depicting the portrait of Cecil John Rhodes by Edward Roworth.

Image: Supplied

THE novelist Olive Schreiner who grew to loathe Cecil John Rhodes, once criticized the dubious friends who perpetually surrounded him. Rhodes flew into a rage, exclaiming "Those men my friends? They are not my friends! They are my tools, and when I am done with them I throw them away.”

It was a revealing indication of how Rhodes operated. When his remarkable powers of persuasion failed, he was adept at providing bribes, share options, directorships or plum positions, certain that any man had his price.

After the failure of the Jameson Raid in 1896, he was not above blackmailing some of the most senior men in British politics, not that they were blameless. If he was going to take the fall, he would not be alone.

Cecil John Rhodes on the verandah of his Kimberley home.

Image: Supplied

An early biographer who had met Rhodes, wrote that his character was cast in a large mould, with enormous defects corresponding with his eminent virtues. Writing in 2005 on the cult of Rhodes, Paul Maylam observed that he was the most written about Southern African figure, attracting (by then) over 25 biographies and many serious researchers.

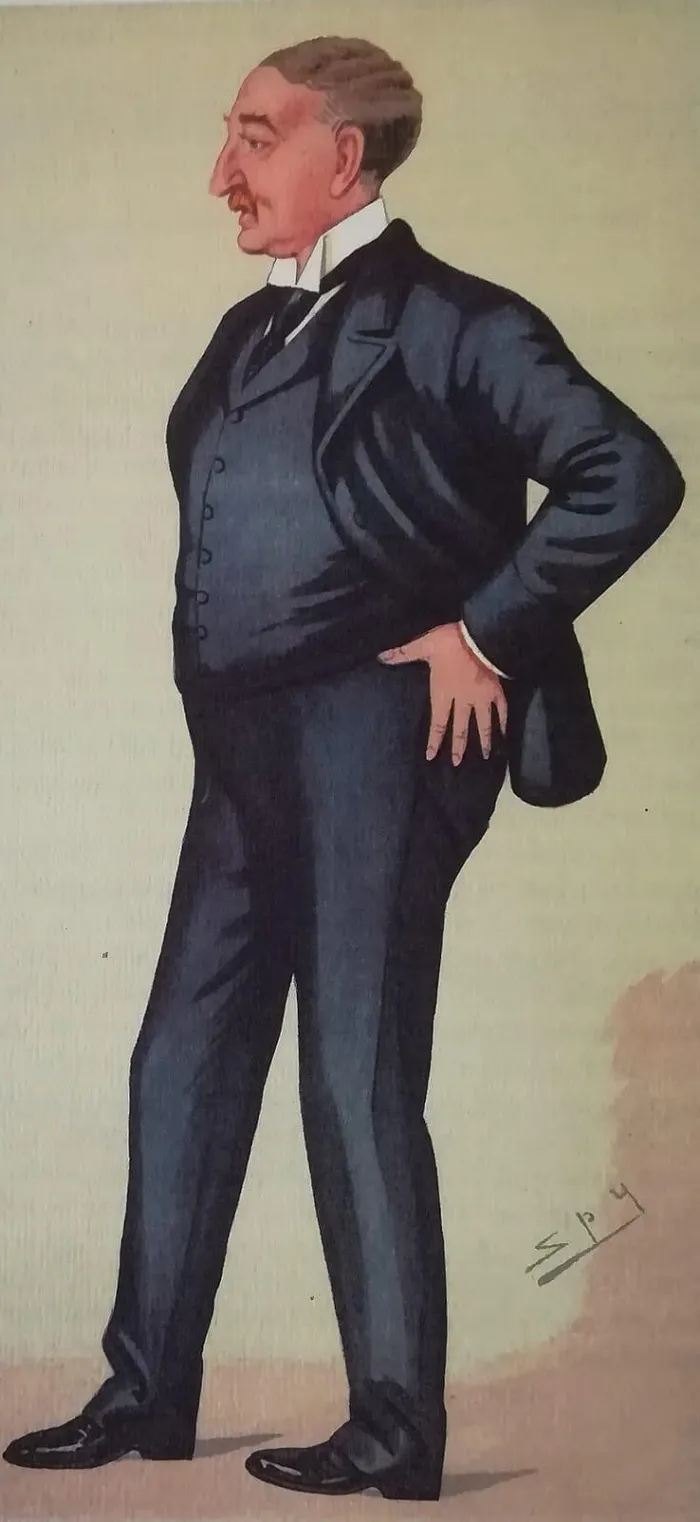

The caricature of Cecil John Rhodes which appeared in Vanity Fair on 28 March 1891. "He was sent to South Africa in search of health. There he acquired wealth, so that he is now not only a robust person but a Diamond King."

Image: Supplied

His latest biographer is an American professor, William Kelleher Storey. In The Colonialist : The vision of Cecil Rhodes (Jonathan Ball, 2025), Storey writes of the celebrity status surrounding Rhodes in the British Empire.

From 1890 until his death in 1902, he was featured in over 79 400 British newspaper stories, with 14 500 stories in 1896 alone. Hundreds of people bought shares in the British South Africa Company just to get a seat at a crowded shareholder meeting.

"The King of Diamonds". A cartoon by F Carruthers Gould depicting Cecil John Rhodes.

Image: Supplied

If not a cult, the fascination with Rhodes possibly lies in the difficulty in understanding the man, his relentless drive and what motivated his obsession "to paint the map red” regardless of the cost. What every biographer faces is the challenge of reducing the diverse segments of his career into a manageable, coherent form. And this of a man who was only 48 when he died, satisfaction having eluded him.

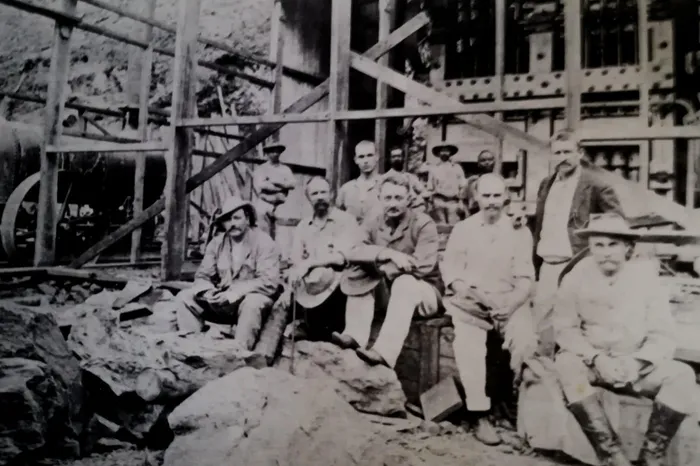

Cecil John Rhodes (left) encamped at Old Umtali in 1897. With him is his secretary, Johnny Grimmer. Standing behind is his cook, Tony Cruz. Rhodes enjoyed the outdoors and never minded rough living.

Image: Supplied

It is often forgotten that Rhodes’s entry onto the South African scene was Durban where his older brother, Herbert, was trying his hand growing cotton in the Umkomaas valley. When the 17 year old Rhodes arrived from England in 1870, Herbert had hot-footed off to the diamond fields leaving his young brother to manage the farm. Herbert came and went, but in 1871 Rhodes left Natal for Kimberly.

Cecil John Rhodes (seated center) on a visit to the Cotopaxi Gold Mine in 1898.

Image: Supplied

His brother returned to the farm, this time leaving his teenage brother to manage Herbert’s claims and speculate on his own behalf. He quickly began to earn money, which he invested. In the light of his dream to build a railway from the Cape to Cairo, one investment was interesting: shares in the Durban-Point Railway.

Hankering for a university education, Rhodes returned to England and began studying for a degree at Oxford in 1873. Aged 20, he was already earning £10 000 a year (the equivalent of about 1.3 million pounds today). His degree was pursued in fits and starts as Rhodes had to return to Kimberly to take care of his burgeoning business interest. He completed his degree in 1881, the year he entered the Cape parliament as MP for Barkly West. He held the seat for the rest of his life.

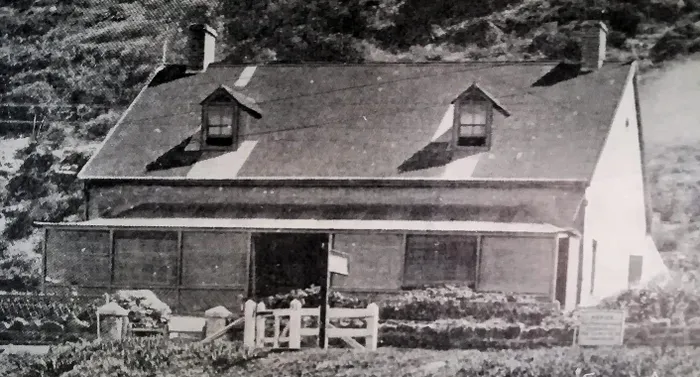

The Muizenberg cottage where Rhodes died on 26 March 1902 aged 48.

Image: Supplied

During the 1880’s, Rhodes with his partners and financiers, bought up claims and rival diamond companies in the name of the de Beers Mining Company. By 1890, it was producing 90% of the world's diamonds. With a monopoly in place, it could control prices by holding back reserve supplies of diamonds.

That same year, relying on his strategically useful alliance with the Afrikaner Bond, he became Premier of the Cape. He was 37. The disaster of the Jameson Raid forced him to resign in January 1896, but Rhodes remained influential in Cape politics.

Cecil John Rhodes's funeral procession passing beneath the Arch at Government Avenue, Cape Town.

Image: Supplied

During the 1890s, the other major source of his income came from Consolidated Gold Fields. Rhodes was less involved with his Transvaal gold-mining operations, relying on his fellow directors. Nevertheless, it was his largest source of income by 1895.

Rhodes used the financial resources of the de Beers and consolidated Gold fields as well as his own funds to further his ambitions in the territory which, until 1980, would bear his name, Rhodesia.

Granted a royal charter, the British South Africa company gave Rhodes and his cohorts the means to gradually steal a country through negotiated concessions or, if necessary, by force. Half a million indigenous people were pushed aside, their land parcelled out to supporters and white settlers, sowing the seeds for future conflicts.

Cecil John Rhodes's funeral procession passing through Bulawayo on the arduous journey to the Matopos where he was buried, April 1902.

Image: Supplied

His approach to African people was both dismissive and critical. His tendency to treat them like children was common in colonial society, but his attempts to disenfranchise those who qualified to vote in the Cape was particularly cynical.

For Rhodes, a non-racial franchise was an obstacle to his larger vision of promoting a Southern African political federation under the British flag. Union was only possible if Dutch fears were allayed as well as those of members of the Afrikaner Bond who kept him in power.

Rhodes kept abreast with technology, on which Storey elaborates. While not making for the most interesting reading, it does reveal how Rhodes’s attention to these details enabled him to become a key figure in South Africa’s transition from a rural economy to an industrialising one.

In his drive for a transcontinental telegraph, Rhodes immersed himself in the technical details of telegraph poles. Aware that wooden poles were vulnerable to termites or being knocked down by elephants, his solution was cast-iron poles manufactured in three sections with an upper tube capable of carrying the telegraph wires.

Groote Schuur, the Cape home of Cecil John Rhodes in May 1910. It was about to welcome Louis Botha, the first Prime Minister of a united South Africa. Union came eight years after Rhodes's death.

Image: Supplied

Labourers struggled to clear routes in an undeveloped country particularly in regions where malaria, dysentery and sleeping sicknesses were rife. On a good day, the telegraph line might advance two or three miles; the transcontinental telegraph was not completed in Rhodes' lifetime.

Rhodes’s ideas about the consolidation and expansion of business resemble those of his contemporary robber barons during the gilded age in the United States. Where he differed from men like Vanderbilt, Rockefeller and Carnegie who preferred to work in the political shadows, was his prominent role in Cape politics and, by extension, British politics.

Behind his back, British officials mocked Rhodes as “the Prime Minister and Foreign Secretary of Great Britain as well as the Premier of South Africa.” It is worth noting that Rhodes, unlike all his predecessors as Prime Ministers of the Cape and many prominent businessmen, was never knighted. Even Jameson, so tarnished after "his" raid and jailed in Britain, was awarded a baronetcy in 1911.

The final ceremony and closing of the grave of Cecil John Rhodes at the Matopos, April 1902.

Image: Supplied

When he was 18, Rhodes drew up his first will. It was an astonishing document. He left all his possessions not to his family but to Britain’s Secretary of State for the colonies to advance the cause of British rule.

His final will went much further, providing endowments for Oxford University, the future University of Cape Town and the creation of the Rhodes scholarships. He also gifted his Cape home, Groote Schuur, to the nation as the official residence of the Prime Ministers of a united South Africa, which became a reality in 1910.

Many a US robber baron burnished his reputation with generous acts of philanthropy. Rhodes did not intend to whitewash his reputation, but as Storey points out, it has had that effect.

Nearly 125 years after his death, the mere mention of Rhodes engenders strong opinions. We continue to wrestle with his complex legacy, uncertain quite where it best fits in the jigsaw of Southern African history.

Although Storey provides another overview, Rhodes remains an elusive figure, an imperialist rather than a colonialist and one whose name has outlasted his vision. One opponent once suggested “Ignore him” to which the MP and editor of the Cape Times, Edmund Garrett, retorted: “One might just as well try to ignore Table Mountain.”

The Colonialist : The vision of Cecil Rhodes is available at all good book stores.

Related Topics: