A photo of "Nanny and Child, Johannesburg" taken by Peter Magubane in 1958 shows a tender moment between a black nanny and a white child de-humanised by the "Europeans Only" sign. The photo is featured in Simon A. Clarke's new book Life Itself: Photography and South Africa.

Image: Supplied

PHOTOGRAPHS elicit emotional responses from the viewer. We respond to the memories preserved in old family snapshots, the visual beauty of a landscape, the joy or grief captured in an interaction between people, we are appalled by the violence of an event or swayed by the propaganda behind a photograph.

Since the invention of the camera, photographs have recorded South Africa through a panoply of social, cultural and political subjects for nearly 200 years. In his new book, Life Itself: Photography and South Africa published by Reaktion, Simon A. Clarke charts that history.

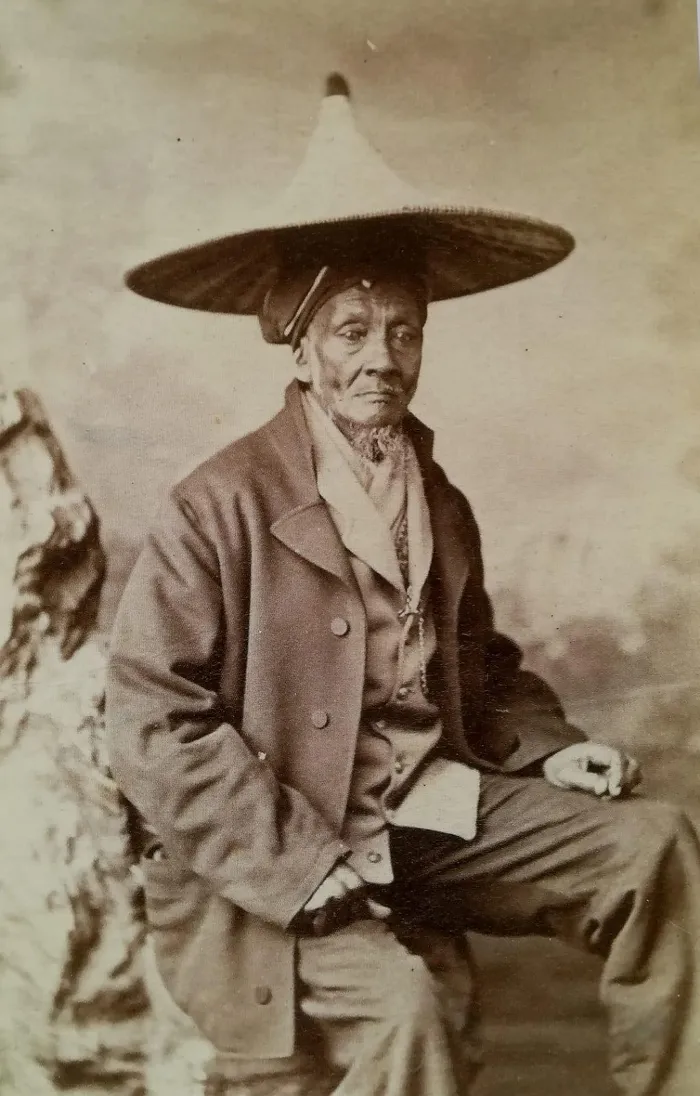

Photo of a carte - de - visite of a Cape Malay Gentleman wearing western clothes with a conical hat, a symbol of his identity, taken circa 1870.

Image: Supplied

A chance meeting in Paris with renowned photographer Roger Ballen aroused Clarke's curiosity in South African photography. New technology was behind its advance and growth, particularly in the 1860s with the carte-de-visite camera which created multiple duplications at low cost. These photos became popular items of exchange among family and friends.

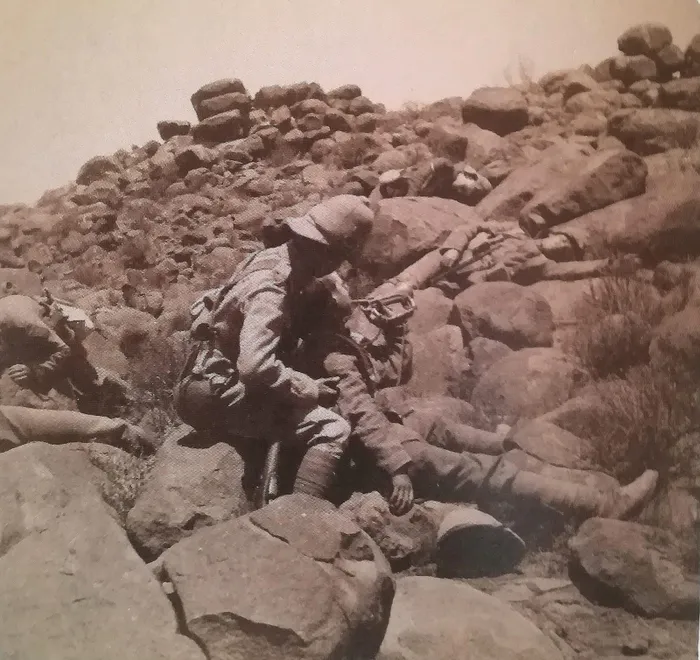

The photo featured in the book Life Itself: Photography and South Africa shows "The Dying Bugler's Last Call, A Battlefield Incident in the Boer War" taken in 1900, with the photographer unknown. There's a theatrical tableau with "dead" soldiers draped over the rocks.

Image: Supplied

Photographic studios sprang up, initially in Cape Town, but soon in other towns. Spotting the commercial opportunities, even tobacconists and watchmakers acquired carte-de-visite cameras as a side hustle, although their photographs were often of an inferior quality.

Individuals or small groups posed in a studio setting where props were on hand. These ranged from plinths and vases to backdrops of rolling landscapes and classical architecture. And how best to display these portraits then in a photo album which became a must- have item.

Natal Natives and Sewing Machine circa 1900s, photographer unknown. The photo shows a Zulu family who appear to have adopted colonial tropes.

Image: Supplied

During the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), reporting of the war was subject to government censorship. Photographers staged scenes, producing symbolic and sentimental pictures such as a dying bugler’s last call amidst the rocky terrain of the veld. The government could not control the imagery for long.

The boer war coincided with further technical advances in which smaller, mobile cameras using film pioneered by George Eastman and Kodak were acquired by ordinary soldiers and newsmen.

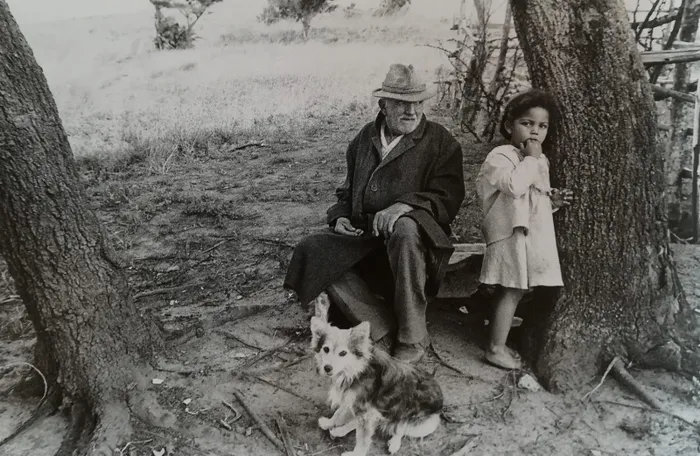

Cecil Green with granddaughter and dog, Margate by Cedric Nunn, 1986. Nunn was disturbed by the racism in his own mixed - race community and the effects of alcoholism and unemployment.

Image: Supplied

As a result, the conflict was extensively photographed with independent observers documenting the realities of war. In stark contrast to the dying bugler is the famous photograph of the dead lying where they fell on the Spionkop battlefield in 1900.

By the end of the 19th century, picture postcards had become a popular form of communication. Initially postcards had only space for an address on the back, but later this was split in two, allowing for a short message.

Postcards of buildings and places of interest were produced in great numbers, enabling holiday visitors to send postcards, many of which were hand-tinted, to friends and family.

The clarion call to arms photo by Alfred Duggan - Cronin in 1920s in Life Itself: Photography and South Africa. In it a robed warrior adopts a heroic pose with a battle horn.

Image: Supplied

Between 1919 and 1928, the self-taught photographer, Alfred Duggan- Cronin embarked on a photographic survey, The Bantu Tribe of South Africa.

Over a twenty year period he travelled 128 000km around Southern Africa. A drawback of his photographs was his tendency to pose his subjects and use props if necessary. His men tend towards the heroic and his women towards the sentimental- a romanticised vision of a vanishing golden age. Nevertheless, his portrait-style photographs retain a striking historical relevance.

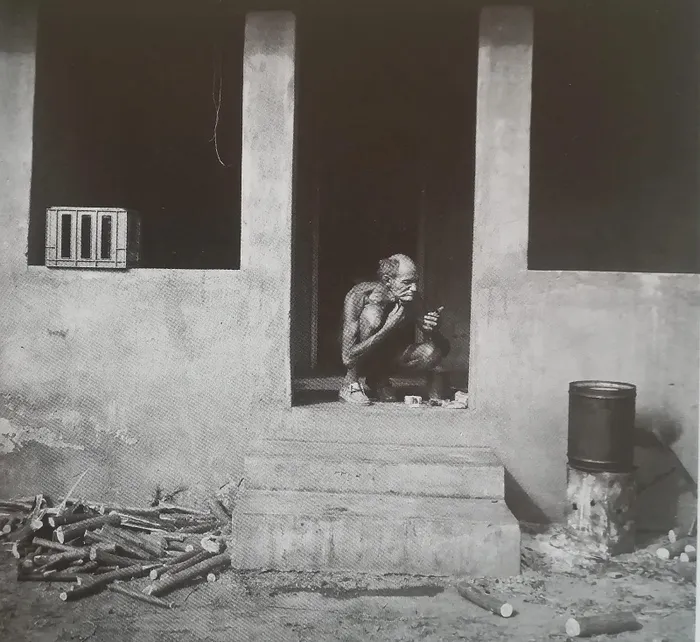

Man shaving on verandah, Western Transvaal photographed by Roger Ballen in 1986. Ballen froze the decay, isolation and faltering existance of the rural dorps (towns) before their extinction.

Image: Supplied

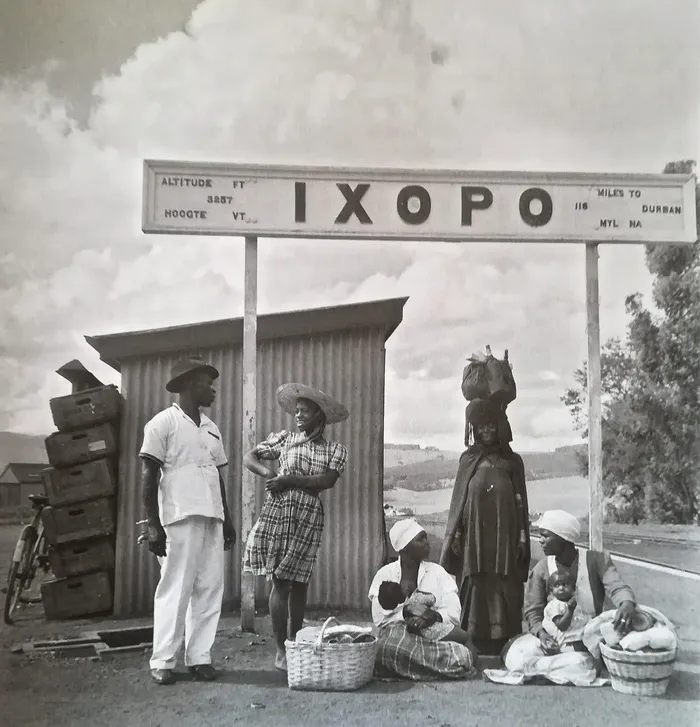

People at Ixopo Station by Constance Stuart Larrabee taken in 1949. An aesthetic photo reflecting the Natal of Alan Paton.

Image: Supplied

Following the success of Alan Paton’s Cry, the Beloved Country in 1948, Harper’s Bazaar commissioned Constance Stuart Larrabee to visit Paton in Natal. Together they travelled to places which influenced his novel. Although the resulting photographs only reached a limited audience, her images added to her reputation as a skilled, perceptive photographer.

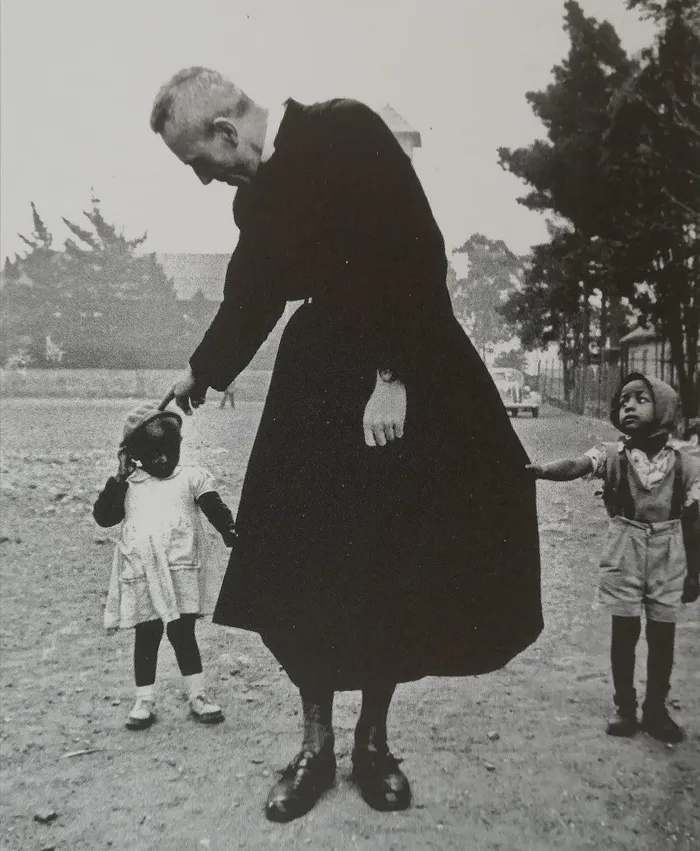

Trevor Huddleston :The Fighting Priest, photographed by Bob Gosani in 1955. It reveals how naturally he engaged with children.

Image: Supplied

From the 1950s onwards, there emerged the era of “Drum” and struggle photographers who recorded township life and the increasingly repressive state response to black demands for equality and political rights.

Images by photographers like Peter Mgaubane, Jugen Schadeberg and Greg Marinovich have become part of South Africa’s understanding of itself.

The depiction of the daily existence of ordinary black people is far removed from idealised images of Duggan -Cronin. Yet both have their value, revealing not only how a photographer views a subject or wishes to preserve it, but also the historical narrative of photography in South Africa.

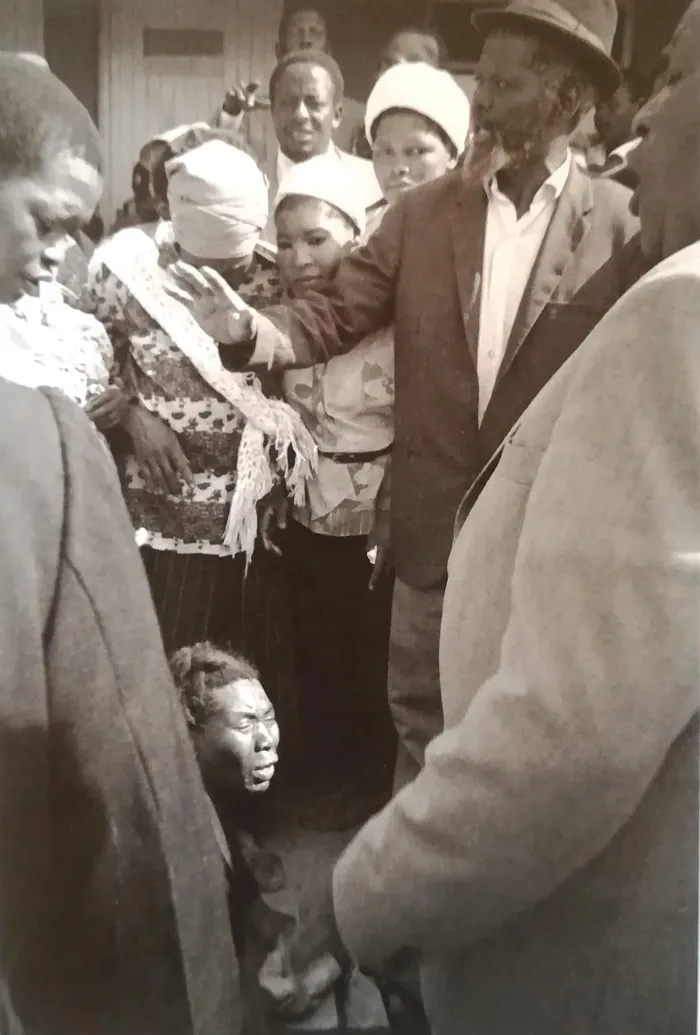

Woman Pleads for Assistance at an anti - eviction meeting, Inanda by Omar Badsha taken in 1982. Facing eviction from her shack, a woman begs for help.

Image: Supplied

If there is one drawback to Clarke's book, it is his emphasis on the bleaker side of South African life when the country was darkened by shadows. Even during the worst of times, there were those random acts of kindness, of children playing sport on an improvised field and, particularly since 1994, those celebrating moments which reveal the warmth and heat of a nation and its people.

Ezisalayo, Field of white plastic chairs taken by Jabulani Dhlamini in 2019. A sea of beached chairs on a field combines realism and abstraction.

Image: Supplied

Photographs can lift the mood as well as force us to stare at an image we would prefer to avoid. As a record of the history of photography in South Africa, Clarke has offered valuable insights into our photographic journey. Equally, it is visually an evocative book with a mix of well-known and unfamiliar images.

Understanding the background behind photographs and their era adds to our appreciation and enduring fascination with the photographic art form.

Life Itself: Photography and South Africa is available at all good book stores

Related Topics: