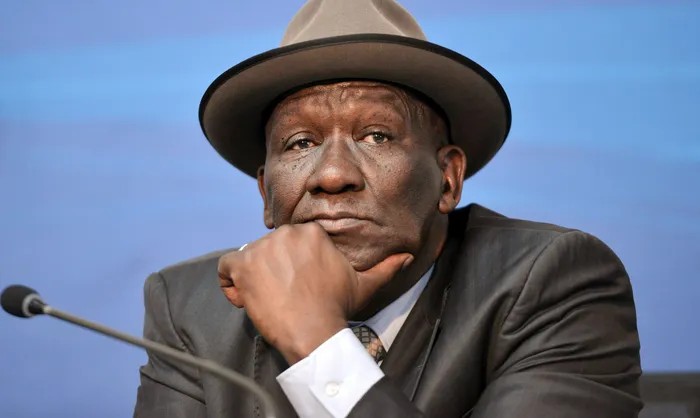

Former police minister Bheki Cele, during the Ad Hoc Committee hearings

Image: Bongani Shilubane / Independent Newspapers

Legal experts have called for more substantial structural changes in the manner in which cases are handled to address the perception that the country’s justice system prioritises the rights of criminals.

They argue that the issue of victim-centred justice is a balancing act between the rights of the victim and those of the alleged perpetrators, adding that the country’s constitution is designed to prevent a recurrence of past injustices, where the accused were persecuted with little or no evidence.

This issue of the rights of alleged criminal versus those of victims recently gained attention after former police minister Bheki Cele testified at the Ad Hoc Committee about the frailties within the justice system.

He discussed the issue of parole, stating that individuals convicted of certain crimes are often released before they are ready, only to reoffend. Cele highlighted the public perception that the justice system tends to focus more on the rights of criminals than on those of victims.

Dr Suhayfa Bhamjee, a Senior Lecturer in the School of Law at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, whose research and teaching focus on criminal law and justice system reform, noted the complexities surrounding these issues.

Regarding parole, she said that individuals may be released when they are not ready due to inadequate rehabilitation.

“Remember that being in prison is not only about punishment; it is also about rehabilitation,” she stated. She added that some individuals might benefit from government mercy programmes for early release, only to later find that they are not prepared for reintegration into society.

She explained that another factor contributing to reoffending is social. “It could happen that crime is the only thing a person knows. Furthermore, in cases where the offender has a criminal record, they find it very difficult to (reintegrate) get a job.”

When discussing victim-centred justice, she acknowledged the complexities involved. Explaining the intricacies of the justice system to victims can be challenging, especially when they have experienced trauma. She likened the situation to “trying to explain the importance of taking swimming lessons to someone who is drowning.”

She emphasised that the changes required to foster a victim-centred justice system are structural rather than merely legislative. “Victims must be meaningfully included in the criminal process, which includes being informed of their rights, consulted on decisions like bail and plea bargains, and supported throughout the trial. While the Victim’s Charter and Service Charter for Victims of Crime provide a framework, implementation remains inconsistent.”

She added that training justice officials to engage empathetically and consistently with victims is essential. “Community involvement is a powerful tool for victim empowerment and crime prevention. When communities actively participate—by reporting crimes, giving evidence, supporting complainants, and exposing offenders—they help shift the justice system from being reactive to being responsive. Community mobilisation also reduces the isolation victims often feel and reinforces social accountability. Civil society organisations, neighbourhood watches, and victim support groups play a crucial role in bridging the gap between victims and the justice system.”

“Restorative justice mechanisms, where appropriate, allow victims to express the impact of the crime and receive acknowledgment—something the adversarial system often overlooks. These processes can foster healing and closure, especially in cases where formal justice feels impersonal.”

“Timely justice is critical. Delays in investigations and trials prolong trauma and erode trust. Strengthening case management, reducing court backlogs, and properly resourcing the National Prosecuting Authority and SAPS are key steps.”

Professor Delano Van Der Linde from the University of Stellenbosch noted that organisations like the Law Reform Commission are working on reforms to make justice more victim-friendly.

He remarked that victims often feel like spectators in their own trials and acknowledged that the law reform is aimed at making the process more victim-centred. However, he admitted uncertainty about what this would look like in practice.

He emphasised the importance of remembering that the rights granted to everyone by the constitution are a direct response to past injustices, where the accused had limited rights, and they are intended to ensure that such situations never occur again.

Related Topics: